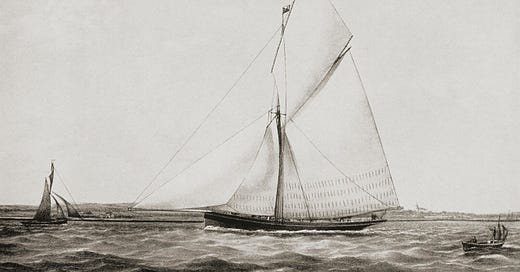

From the late 19th into the mid 20th centuries William Fife III created the most excellent yachts (sail boats) from his small yard on the foreshore of the Ayrshire village of Fairlie. These yachts set a new standard for fast sailing excellence. Albert, the Son of Queen Victoria owned and raced one of these ‘yar’ craft. For boats are still highly sought.

Andrew Sangster watched from the Buckingham Palace parade grounds as the cortège for the late King Edward VII began to process slowly away, heading towards the black-clad crowds of Londoners. The trumpets of the Royal Irish Fusiliers military brass band played Handel's Dead March from his oratorio, Saul,

‘From this unhappy day

No more, ye Gilboan hills, on you

Descend refreshing rains or kindly dew,

Which erst your heads with plenty crown'd;

Since there the shield of Saul, in arms renown'd,

Was vilely cast away.’

The world had changed utterly not just today, but during Andrew's lifetime, from his birth in far-away County Bute during the reign of the great Queen Victoria, through the short reign of his master and skipper - ever the genial and laughter-filled 'Bertie' when away from his gloomy mother. War trumpets were soon to be heard across the continent, as Europe gathered to say its last farewell to this genial king and his gentle era.

Andrew had turned many a blind eye and deaf ear to the prince's, then later the king's, shenanigans, as had Albert Edward's long-suffering wife, Alexandra. He had been on the yacht with the prince when news of his first royal son's death reached him. Andrew was a man acquainted with grief, having lost his father and eldest brother, and had sat with the grieving prince when all others on deck were at a loss. Providence also found them together when the prince's son, also Albert, died following his betrothal. Again, it was Andrew who comforted the older man as he had done before for his own mother and sister in Millport.

"So many years ago now", he mused as the long line of carriages of the soon-to-be-gone European monarchies from the Russian and German Empires, Italy, Monte-Negro, Serbia, Romania and a dozen other countries' trundled noisily past. He watched as the black moving-image cameras turned their huge single eyes upon the coffin, the golden glory of the carriages, and the be-feathered sable horses strutting, tails-up, for the long drive to Westminster Hall where the Archbishop of Canterbury waited, dressed in his glorious robes.

Andrew Sangster returned to the palace, where a servants' funeral lunch had been prepared. Many of the men, none of whom had wept a tear at the old queen's death, were wet-eyed. His wife, Victoria, sat with the women who were all sobbing. Andrew turned a wry smile to the man next to him, cocked his head at the women, and the man smiled back. Victoria Sangster regularly nagged him about Bertie's lifestyle and about the women - some of whom were high-born - who frequented his company.

It was true, the dead king had been no saint. But the men each knew that he was pleasant company, lacking stuffiness, and was as prone to joking and laughter as anyone other man in England. Now, the women were weeping for him. Death. The great leveller for the great and good, the unimportant and the bad.

A week later, following the reading of the late king's will, he found himself back at Cowes, on board the Royal Yacht Britannia. It had been Bertie's decision, often told him on board during racing, that the care of the yacht would always be in the hands of Andrew Sangster. He shouted, "Ready the mainsail. Cast off the lines. Secure warps and fenders." The beautiful yacht moved slowly as the sail filled, gull-winging from the seaward breeze.

Once out of port he was in his element as he manoeuvred the yacht through the Solent and westward into the English Channel. "Fit the cunningham. Tighten the halyard. Trim the jib." he shouted. "What's a cunningham?", asked the apprentice standing at his side, the yet-beardless John Cornwallis. Andrew lent over, "Here, tak the wheel, John. It's what you English call a kicker." His mind, ever at peace on such a clear windy day, drifted back to the Clyde, to his home, and the family he left behind to seek his fortune with Mr Fife of Fairlie and then with the Prince, who now was buried in St George's Chapel in Windsor, safe from further scandal.

"If a man wants to think, he should have his horse or boat readied." It was a regular saying of the old king. As was, "Sailing and riding both steadied the mind from - and for - important matters of state and matrimony."

"Tak us on till Trinity Landing", he instructed young Cornwallis. The lad was dark haired and dark eyed, just like Andrew's late brother, James. He stepped away from the wheel and took out his clay pipe, filled it with Cavendish Golden Flake, lighting it with a Lucifer. The day was turning out fine as the gentle mist cleared to allow the early sun through. Oilskins and felts were soon put to one side as the crew emerged, angelically, in whites.

Sixteen years ago he had come into Prince Bertie's service. Six years before that his father and brother were lost at sea. He couldn't remember their faces, but the Spanish black hair and eyes, and their dark skins that tanned so easily in the east coast sun remained with him. "Hair as thick and full as Absalom's", he thought as he re-ran the moving images of the king's funeral through his head.

The family were one of many in the village of Enster in East Fife with these dark, swarthy looks. Quite unlike their paler Pictish peers. Generations descended, so it was said, from sailors who came ashore from a Spanish merchantman which floundered on its flight from Drake's victory over the Armada, going down as it headed down the channel between Crail and the Isle of May. “Probably caught in a North Sea squall which drove it onto the rocks of Enster Easter", he mused. The sailors had landed in the neutral Scottish port, captured the hearts of local maidens and widows, bringing Spanish blood to life in the East Neuk.

He had been born into poverty in a decrepit house near the Dreel Burn. His mother and father had begun their lives together, as fishing families always did, during the herring season. The men brought in the catch to a port where the young women gutted and packed them to be sold by merchants to the army quartermasters. The giggling girls were watched closely by the stern widows to ensure there was no fornication. But, they also kept an eye on the men, particularly for a strong widower. The men came in ships from everywhere and anywhere in the British Isles and the women travelled around the ports in groups, earning good money for their families - and to start new families.

Every summer the East Neuk boats would sail to Rothesay and other lower Clyde ports, first to sell their fish or wed, then they came with their families as the new concept of a summer holiday expanded. Some, like Andrew's family, had abandoned the cold east coast house that was home and had stayed to fish the rich waters of the balmy Clyde where the weather was, unlike the North Sea, predictable.

But, it was never a safe occupation. They say his father and brother's boat may have gone down west of Kintyre in the open sea. Perhaps they were taken by Irish or Manx pirates. Or waylaid by a passing Royal Navy ship. Whatever happened, they were never seen again. Six months later there had been a Requiem Mass at the Episcopal Cathedral of the Isles in Millport. His mother had taken to religion, like so many fisher families during the high Anglican Revival, bypassing traditional Presbyterianism and the new Evangelicalism. The local Anglicans ran a poor support scheme for fishing widows which had kept the family going until Andrew was of age for an apprenticeship.

"You're not going to sea. And that's the end of it." His mother had been calm but determined when he told her of Mr Fife's offer to work in his boatyard across Fairlie Roads on the mainland. "I won't, mama," the boy replied, "It is only building and trialling them in the Clyde. Mr Fife won't let a costly master craftsman, which I will be, become lost at sea." He knew he shouldn't have said that last part. His mother turned her face from him. But she knew he was determined, so, stretching out her hand she took his, pulled it to her face and wet it with her warm tears. "Don't die at sea like your father, John, and your brother, Peter, did. Promise me, Andrew. Promise me." She looked up at him. Loss had taken her early into middle age. "I promise, mama." And he meant it. Even if he could not guarantee it.

Mr Fife's yachts were famed in the racing world. His father and grandfather had also designed and built their yachts on the shingle beach at Fairlie for well over a hundred years, but it was Will Fife's design skills that created some of the greatest yachts ever to sail and race. His fame grew. He came to Prince Albert Edward's attention as co-founder of the Royal Yachting Association. Sir Joseph Lipton had invited the prince to come aboard his Fife yacht, Shamrock, as the crew was being paced for the America's Cup. Lipton's yacht lost the race, but it won the prince's heart.

Andrew was working on some feature scrollwork when Mr Fife brought over the visitor one day. "Andrew, this is His Highness Prince Albert. You're going to work on his new yacht. How do you like that?", he asked. "As long as he likes dragons!", the apprentice responded. Silence fell. The prince laughed, "I like this boy. Can he sail?", he asked. "Why, yes, I can. I've been sailing all my life. Yachts are just sleekit fishing boats. But more fun to be in.", Andrew replied before Mr Fife could respond.

The prince liked the boy's candour and lack of fawning, and so Andrew became one of the crew for the sea trials after launch.

"Is it as fast as you would have expected?", the prince asked him one day as they passed through the Cumbrae gap. Andrew replied plainly, as ever, "Faster. I am a bit concerned that it tends to pitch more than most at the bows in a rough sea. Its a lighter boat though as we used knotless pine on the finishes. But, this means most of the weight is lower down, so the boat has greater stability when hit by a big wave on the port or starboard hull."

The prince pondered this, "So it is less likely to turn over?" At this the boat hit a big wave head-on just off Steadholm Point as they turned eastwards and caught the breeze, and Andrew flew past the prince and was overboard in a second.

He clawed at the water, realising that he had left his cork lifeboat in the cabin. Fool! He had been distracted by the excitement of being back with the affable prince and back at sea on what he always thought of as his yacht, filled as it was with his carvings, including an amazing new Fife dragon. His co-workers had started to call them young Fyfe's dragons.

Verses of poetry resounded in his head as the oxygen in his lungs failed,

Pride comes before a fall

He would have screamed, but if he could, who would have heard him beyond the porpoises, crayfish and mackerel?

From the belly of death I cried,

flung down, deep into the sea;

floods rolled over me,

Breakers and billows swept over me;

I was flung out of sight,

Never to see land again.

Waters closed and choked me,

The deep has rolled me up.

Seaweed will wrap my head.

As I sink to the roots of Caledonia's mountains,

To the land whose bars close forever ...

As the world went black a grappling hook caught his shirt and hauled his body to the side of the boat. "Your highness, take tent!", a sailor shouted as the prince leaned over the rocking boat. The boy had been right, the boat was fast, prone to a large bow wave, but impossible to overturn. Bertie had taken charge, ordered the tack, keeping an eye on the boat and the point where the boy went down. When the boat had turned they found the body bobbing near the surface. "Well, I never saw a body float without a lifejacket before!", the prince exclaimed as he leaned over, grabbing the boy by his thick black hair, helping manhandle the wet body back on board.

He lived, thanks to the work of two of the crew members to empty his lungs and warm him up with dry clothing. And a ration of 57% proof Admiralty recipe Royal Navy rum! The prince ordered a bottle for each man on board on their safe return.

"I'd like to thank you, Your Highness, for saving my best apprentice. I don't know what I'd do without him", Mr Fife said as they sat with Lord Glasgow and the Earl of Airlie for dinner in his extensive villa in Fairlie that evening.

"Well, I think you might have to, Will. When the yacht is ready I'd like the boy not just to deliver it to Cowes, but I'd like to retain him in my service with the yacht. No-one know the yacht as he does. He's young yet, I suppose he might even remember to put his lifejacket on!" Gentle laughter passed round the room as the men smoked their Cubans and tasted the Port wine.

"But, what do you make of how we recovered him? I saw him go down like a stone, and it is a good 10 fathoms off Waterloo Point," the prince pondered.

"Dinna ken what to make of that, Your Highness. Bodies simply don't float. Well, not for several weeks, at least. Men lost south of the Cumbraes have been know to wash up in Antrim or even as far away as Ramsay. What did you make of it, your highness?", Mr Fife was getting nicely warmed by the wine and company.

"Bertie, Will. Bertie will do," the prince rejoined. There was more small laughter.

"You know, Will", the prince took a third refill of the fine port, "If I had had time to think about it, but things happened very suddenly, and it was speed that was required to save the boy's life. If I had been watching from beyond, I could have sworn - I'll be damned! - that the porpoises were pushing him upwards and towards the yacht. Keeping him afloat and visible." No-one spoke as they pondered this image.

"Did you know the boy had already lost his father and brother at sea?", Will asked.

"No!", the prince exclaimed.

"We promised his mother he'd not drown. I told her right there as she stood in front of me on the day he started his apprenticeship. If he had died, I don't think I could have faced that woman. She was a troubled-enough soul as it was." The words of the great yacht designer floated in the air as the men sat to digest the meal and their stories of the sea.

It was the prince who broke the reverie, quoting an old poem of a drowning man, returned from the sea,

What I have vowed I will perform,

but 'tis the Eternal who delivers.